Feminism: a word that never fails to make people uncomfortable and unsure about whether they want to identify as one. Since the birth of the movement, society and those looking to uphold the status quo have stereotyped us with a whole range of negative traits. Within Christian circles any mention of the word can mean an awkward silence, or mutterings about how ‘extreme’ it all is. I asked my followers on Twitter to list the misconceptions and myths they most commonly hear about feminists. I displayed the results in a handy word cloud:

So how did these misconceptions come about? And why do they persist? Let’s do some myth-busting.

Man-haters

Officially the world’s number one misconception about feminists. No feminist stereotype would be complete without anti-men sentiments, possibly even the idea that the world would be better off without them. It’s crucial to distinguish here between ‘having a problem with all men’ and ‘having a problem with the things that some men do’ because the latter is more realistic.

But what feminists tend to have the biggest problem with is patriarchy. That is to say, the social system that upholds male rule and privilege. Why is this? Well, because, as the Wikipedia entry for ‘Patriarchy’ tells us: “Historically, patriarchy has manifested itself in the social, legal, political, and economic organisation of a range of different cultures.” And when men run the show, women end up treated as second-class citizens. Most feminists would acknowledge that patriarchy is actually bad for men too as (among other things) it promotes restrictive gender roles that place certain expectations upon men and women.

Anti-family/children/stay-at-home-mothers

In decades gone by, a seemingly anti-family rhetoric was more prominent in mainstream feminist thought. There was a good reason for this – the fact that back then, ‘the family’, marriage, and motherhood represented something quite different and meant very different things for women. A woman had little in the way of rights or status – things such as opening a bank account or buying a car needed her husband’s permission – or her father’s if she wasn’t married. Laws surrounding equality had yet to be enacted. Rape within marriage was not yet illegal. Women with abusive husbands felt unable to leave them thanks to lack of economic power, lack of support, and the unsympathetic attitudes of the authorities. Even in the 19th and early 20th centuries feminists were stereotyped as unattractive ‘old maids’ who were going against what was ‘natural’ for women.

It was clear that these factors were contributing to the oppression of women and that change was needed. Feminists have long campaigned for a woman’s worth to measured by factors other than whether she is married and has children. When you take these issues into account the anger of feminist activists was certainly justified, but more conservative critics didn’t see it that way, and the ‘anti-family’ stereotype was born. Even today, a woman’s ‘success’ in life is often tied up in whether she has a husband and children. Women who don’t fit this mold are often seen as deficient, sad, and worthy of our pity. It’s important that our definition of what it means to be a woman isn’t so narrow.

Wish to dominate or rule over men

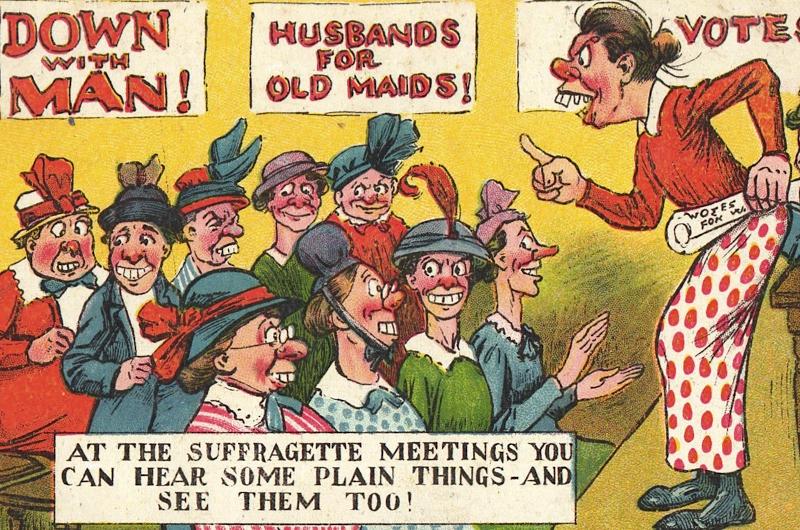

An age-old stereotype that can be seen in anti-suffragette propaganda, the image of the feminist as a believer in the subordination of men has certainly been persistent. In the 19th century, drawings depicted women who wanted the vote and property rights as dominating their weak and feeble husbands. One cartoon showed ‘the future of Parliament’ – a room full of women discussing ‘Man and how to treat it’ – showing how absurd it was considered at that time that women might have a say in the political process.

Today, the idea that feminists are in favour of female superiority is often the first thing that people who don’t know very much about the feminist movement want to talk about. Here’s the thing: according equality to women does not mean taking rights away from men. It’s about levelling things out, not reversing a bad situation and somehow punishing men as a result. It’s a common belief that when less privileged groups achieve more equality in society, those who are more privileged see it as an attack – this can be applied to other areas of oppression such as economic status and race too.

Anti-God

It stands to reason that a patriarchal organisation would accuse feminists of going against the Bible and God’s plan for women, right? Actually, it’s not that straightforward. The first wave of feminism had profoundly Christian roots and a heart for justice inspired by the abolitionist movement. Some activists spoke out against interpretations of the Bible that placed women only in a traditional role and prevented them from preaching or holding positions of authority in the church. Conservative churches and individuals stepped up their efforts to discredit feminism again in the 1970s when societal changes and calls for a move away from women being defined as wives and mothers angered them. It was out of this atmosphere of unease that some lifestyles, anti-feminist Christian organisations and even groups of churches were born – for example the Christian Patriarchy movement.

However it’s important to realise that there are many feminists who want to remain faithful to Christian teaching at the same time as campaigning for gender equality. The Bible is not explicit on what roles women should occupy in society, but it is explicit about equality, dignity, and our treatment of the marginalised.

Homogeneous

I’ve often heard people say that they’re not sure they want to identify with feminism because they don’t agree with the things that some feminists believe – things they might see as extremist, for example, or going against their religious beliefs. There’s a tendency to assume that feminists are a homogeneous group, that there is a particular party line on all issues. But like all philosophies, political beliefs, and religions, there is a wide variety of opinions and many schools of thought. Put it this way – most of you reading this would want to distance yourselves from the behaviour and beliefs of certain Christian churches or individuals. But you haven’t renounced Christianity yet, right?

Of course there are things that pretty much all feminists agree on, but there are lots of things that they debate too. And this isn’t a bad thing. People come from different places and have lived different experiences – it’s bound to be that way. I’m not going to deny that there is a fringe of feminists who have genuinely extreme and unpleasant views, but they really are just that – a fringe, much the same as in other philosophies and belief systems. Don’t let them put you off saying you believe in gender equality.